Gove challenged over exam coercion

WORKERS, OCT 2012 ISSUE

AS WORKERS WENT TO PRESS a legal challenge was being launched against exam regulator Ofqual for its refusal to re-grade GCSE English papers in England. Six teaching unions, 113 schools and 13 councils have combined and written to exam regulator Ofqual and exam boards AQA and Edexcel threatening to seek a judicial review.

The challenge says Ofqual’s refusal to re-grade flawed exam results from June contravenes “the cardinal principle of good administration that all persons who are in a similar position should be treated similarly", adding that the decision is "conspicuously unfair and/or an abuse of power, breaching (without justification) the legitimate expectations" of students who sat the examinations.

This August, for the first time in 24 years, the number of students gaining a C in English dropped. Schools and pupils were shocked as all the indicators pointed to another year-on-year rise. Because some pupils had taken the exam earlier, with results published in January, schools were able to gauge accurately the range of marks necessary for a particular grade, including the important C grade – a C in English is a pre-requisite for progression to higher levels of study, and a requirement for apprenticeships and other points of entry to the world of work. Secondary schools are rated on the percentage of their students achieving C and above.

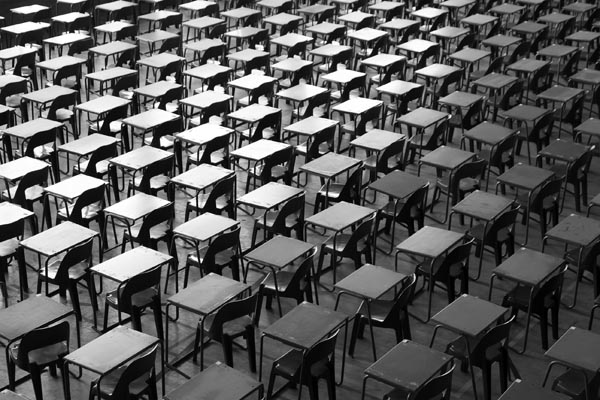

Photo: Stephanus Le Roux/Shutterstock.com

Had teachers got it wrong, or was something else afoot? Schools smelt a rat. It transpired that analysis of the January results had indicated more students than ever would be likely to achieve a C or above in the June exam. Accordingly Ofqual made the exam boards change the grades so as to drive down the anticipated success rate in June, despite examiners believing they were fair and backed by compelling evidence. But not a word to the schools – hence the outcry in August when tens of thousands of pupils were suddenly deemed failures.

Education Secretary Gove admitted that students were treated unfairly, but when pressed to order re-grading of the June exams with the January grade boundaries, insisted such a change was beyond his remit. His suggestion that the pupils could resit the exams in November condemned them to an additional and unnecessary year of uncertainty and lost opportunity.

Direction

Infuriatingly for Gove, Welsh Education Secretary Leighton Andrews directed the Welsh exam board to re-grade the June exams. 2,400 students saw their grades rise, 1,200 of them from D to C.

The backlash after this blatant engineering of results may yet prove to be Gove’s undoing. He has united all corners of the educational spectrum with his cack-handed interference and wilful disregard.

Playing out in the background is an ongoing debate about GCSEs, which replaced O-levels in 1987. O-levels were awarded on the basis of a single examination at the end of a course of study, whereas, with GCSEs, modules of study in a particular subject are assessed throughout the duration of the course.

There has been relentless pressure on schools to achieve better and better results for their own survival. Crude league tables and Ofsted make this inevitable, so the year-on-year rises in GCSE results come as no surprise.

For some, O-levels bring back fond memories of academic students going on to sixth form and university while their less academic (or less well off) peers populated the mine, the mill and the shipyard.

Now Gove’s new exam – the EBacc – will provide a qualification for some, but nothing at all for the rest (those who find the exam “difficult” will leave school with only a statement of achievement). With their plan of mass youth unemployment, why bother to educate those young people at all?

Gove staggers about from one debacle to another. In the past 37 years there have been 18 education secretaries, one every two years on average. Why is this one still here? ■