A long and bitter struggle in the winter of 1989-1990 laid the foundations for the current transformation of ambulance workers into paramedics…

When ambulance workers drove a coach and horses through government pay policy

WORKERS, OCT 2010 ISSUE

A long and bitter struggle in the winter of 1989-1990 laid the foundations for the current transformation of ambulance workers into paramedics, by building the understanding, confidence and organisation of the workforce. We should never forget the dispute or the people who took part, and never permit the airbrushing of it out of our history.

In the small hours of a cold late February morning in 1990 at a South London, Elephant & Castle government building, a deal was struck between the unions representing ambulance workers (NUPE, COHSE, NALGO, GMB and T&GWU) and the Department of Health, after a marathon meeting throughout the night. This deal was to be put to ambulance workers as a way of trying to resolve the six-month-old national ambulance dispute.

A very tired Roger Poole, chief negotiator for the Joint Unions, came out on the front steps and, facing a forest of microphones, television cameras and Press, made his famous (infamous) “Coach & Horses” speech: “Today we have driven a coach and horses through the Conservative government’s pay policy!”

The proposal inside that coach included a 16.9 per cent increase over two years, an extra 2 per cent for productivity, increases in London Allowance, and funding to develop the new role the paramedic for the future. The increases were to be backdated, with part of it paid as a lump sum.

In return for this the unions agreed, under duress, to withdraw a major part of their claim – an annual pay formula linked to the pay systems of police and fire-fighters.

The full original claim from 1989 was:

- £20 a week increase to bridge the gap between ambulance staff and the fire service;

- A formula to determine pay in the future;

- An overtime rate for overtime work;

- A reduction in the working week and 5 weeks’ holiday;

- Better pay and holidays for long service;

- An increase in standby pay.

By 13 March 1990 over 81 per cent of ambulance workers nationwide had accepted the offer.

|

So, after six months of a hard-fought dispute starting in September 1989 with a rejection of a 6.5 per cent pay offer amid an overtime ban and a work to rule; with police and the army on the streets doing ambulance work; Christmas and New Year without pay; marching and demonstrating in London’s Trafalgar Square with 40,000 others; collecting money in buckets from a very generous and supportive public; being locked out of ambulance stations; breaking back into ambulance stations for “sit ins”; being called “van drivers” by the then Health Secretary, Ken Clarke; taking 999 calls straight from the public at stations in a kind of Soviet/commune atmosphere; presenting a 4 million plus signature petition, which at the time broke the British record for the largest ever collected (and may well still be the largest for an industrial dispute); having thousands and thousands of other workers stop work in support on one lunchtime: after six long bitter months…

At 07.00 on the 16 March 1990 ambulance workers across the country went defiantly and proudly back to work.

Those who can remember the ambulance dispute of 1989-90 will also remember the bad taste in the mouth that it left. Although the political, the moral, and the public argument was won, the six-month dispute ended with a settlement that didn’t move ambulance workers on very far as a profession worth joining or working in.

One reason for this was because a major component of the pay claim that year had been the establishment of a pay formula. But this was dropped.

The formula would have seen pay and terms and conditions improve year on year without an annual fiasco, and without putting patients at risk. It would have brought stability and professionalism into the ambulance service and at last seen ambulance staff gaining the respect that they deserved and were entitled to.

In addition to this, a pay formula would have been a way of creating a proper career structure based on training and experience.

Because of lessons learned from the dispute and a more disciplined, organised union (particularly Unison, particularly in London) ambulance staff now work within a modern, professional Ambulance Service alongside and among staff whose training, skills, career choices, pay and terms and conditions could not even have been dreamt of by the workers who stood at the picket lines and fought for their future back in 1989/1990.

|

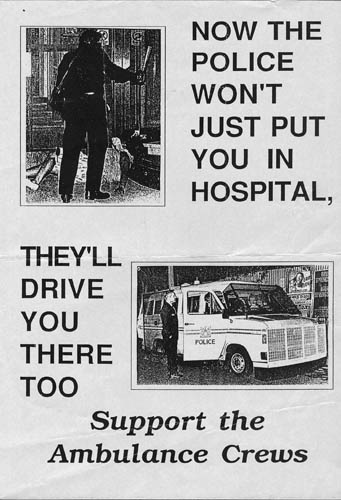

| Poster produced by ambulance workers during the dispute. |

Ideas and vision

All this did not come about by accident, nor was it simply given to ambulance workers. All this did not happen in a void. These gains and improvements are attached to an invisible umbilical cord stretching right back to the ideas, vision and strength of character of workers who went through the dispute and came out the other end still optimistic and positive.

The experience of the dispute certainly cleared a lot of heads and gave firm views of what trade unions ought to do and where ambulance services ought to be. A seed was planted in that national dispute that has been watered, tended and lovingly cultivated by workers who went through it. A belief and confidence sprung up alongside a determination that ambulance workers and ambulance services would never go back to those times ever again.

Clarity emerged that the police and fire service were not role models in the sense of positioning ourselves within the public services as many politicians wanted. Ambulance staff knew that their position should be at the heart of, and central to, the National Health Service and that the pursuit of some kind of ‘joint rescue sector’ with the other emergency services was a red herring.

The dispute taught workers that with organisation and discipline they could stand on their own two feet. They have done that and their achievements in the ambulance service are many.

Agenda for Change is the modern version of the pay formula that was brushed under the table at the Elephant & Castle 20 years ago. Finally rescued, resuscitated and brushed down, it has not only brought parity with the police and fire service but has surpassed them.

Training

The need for properly trained paramedics was an idea that started to grow in the latter stages of the dispute when the unions were not only fighting a pay claim but, with their members, fighting for the survival and future of ambulance services and ambulance workers. Ambulance workers deserved better, the public deserved better and patients deserved better.

The union’s full involvement in decision making was vital if they were to drag poorly funded, poorly paid, poorly appreciated ambulance services into the modern age, and although it took a further ten years to start the process of partnership working as one way to protect public services (a lot of wounds were still raw), the battlefield relationship between management and staff in 1989/1990 and before made it plain that things had to change.

One of the greatest visible links between the past, present and future of ambulance services is currently back at the Elephant & Castle. Who would have thought that the very building where that deal was struck in the early February morning of 1990 – the Department of Health’s Hannibal House – would now be used as a training centre for London Ambulance Service at which student paramedics are trained at the start of an innovative three-year course?

How ironically full circle that the same rooms in the same place that had witnessed many a difficult meeting in the midst and struggle of a national ambulance dispute to improve work, pay and job security, are the very rooms now being used to train the future!