Deemed not respectable enough by the labour movement’s later historians – they dismissed “Luddites” from their accounts...

The early 1800s: national workers’ organisation arrives

WORKERS, SEP 2013 ISSUE

It was during the first half of the 1800s that a nationally organised working class first emerged throughout Britain with centres in for example Sheffield, Birmingham, Leeds, Nottingham, Glasgow and the West Country.

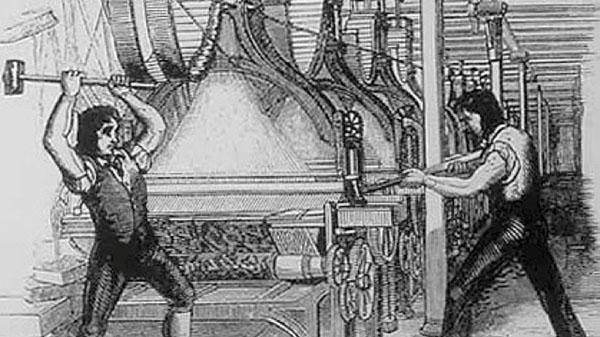

Contemporary portrayal of machine-breaking.

The early vanguard were the clothing workers, known as “croppers”, who had become strong enough to enforce a closed shop in many of the workshops in Wiltshire and Yorkshire. Parliament by 1806 had been warned that a croppers system “exists more in general consent to the few simple rules of their union”. Until then croppers had evaded all chance of conviction for “combination”. They had formed themselves into a “club” and had accumulated over £1000 to provide for their members in the event of sickness preventing them from being able to work.

The croppers were also in correspondence with the cotton weavers, who through combination had formed an impressive nationwide union that existed from 1809 to 1812. With its centre in Glasgow it had strongholds nationally including Manchester and throughout Lancashire, Cumbria, Scotland, and Carlisle.

Strike

By 1811 the weavers could raise 40,000 signatures in Manchester, 30,000 in Scotland and 7,000 in Bolton. A disciplined and well supported weavers’ strike from Aberdeen to Carlisle then took place in 1812 with the aim of securing a minimum wage. The strike was eventually broken when the Glasgow leaders were arrested and jailed, with sentences ranging from four to eighteen months. The ruling class feared Britain was on a direct road to an open insurrection, so unions had to be broken.

Responding to what had happened to the Glasgow weavers, Luddism, which had been first deployed in Wiltshire in 1802, then took up the baton. It moved out from the grievance of the croppers to more general revolutionary aims among weavers, colliers and cotton spinners. “It is a movement of the people’s own” was how William Cobbett, a political commentator of the day, described it.

The Luddites are normally portrayed as a lunatic irresponsible fringe that stood in the way of progress by trying to wreck factory machinery. But Luddite opposition to machinery was far from unthinking. Along with machine breaking they made proposals for the gradual introduction of mechanisation, with alternative employment to be found for displaced workers, or by a tax of 6d. per yard upon cloth dressed by machinery, to be used as a fund for the unemployed seeking work. All of the proposals were rejected by the employers.

The focus in portraying Luddites simply as machine breakers was initially founded by Fabian historians (the Hammonds and the Webbs) writing in the late 1890s and early 1900s. The Fabians took it upon themselves to pioneer the written historical study of the early labour movement. Their aim was to portray the period 1800 to 1850 in the narrow context of the subsequent Parliamentary Reform Acts used to widen the vote from the 1860s onwards and to link this to the growth of the Labour Party during the early 1900s. They did not see Luddites as satisfactory forerunners of the “Labour movement”. So Luddites merited neither sympathy nor close attention.

Liberal and conservative historians decided among themselves during the early 1900s that “history” would deal fairly with the Tolpuddle Martyrs but the men executed for Luddism between 1812 to 1819 should be forgotten – or, if remembered, thought of as simpletons or people tainted with criminal folly. The Fabian view persists to this day in many quarters. But the facts tell a different story.

Politics

Rather than simpletons “Luddites and Politics were closely connected” shouted Thomas Savage in 1817 just before he and five other Luddites were executed at Leicester. In November 1816, 14 Luddites went to the scaffold in York defiantly singing “Behold the Saviour of Mankind”. Asked whether the 14 should all be hung simultaneously on a single beam the presiding judge replied, “Well no, sir, I consider they would hang more comfortably on two.” Their relatives were not allowed to bury the bodies.

A similar thing happened in Nottingham when 3,000 mourners went to the funeral after the hanging of Jem Towle, a leading Luddite – but magistrates prevented the funeral service being read. A friend later said, “It did not signify to Jem, for he wanted no Parsons about him.”

The Luddites, from 1812 to 1819, were the first to launch the agitations which led to the 10-hour movement during the 1840s. It was they who said that if a new machine were to be introduced the extra value generated should mean workers do fewer hours for the same or more pay or be redeployed. In particular they argued that child labour should be curtailed in factories as part of negotiating the introduction of new machinery. In “polite circles” at the time, factory child labour was considered “busy, industrious and useful”.

The employing class, its government and its snivelling apologists hated the Luddites so much because of their thought-through views on political economy. It was these ideas, not the cowardly gradualism encouraged by the Fabians, that eventually led to self-confident British trade unionism. In keeping with the recent victory over Napoleon and his designs on Europe, the call by workers in 1816 was ‘‘Ludds do your duty well. It’s a Waterloo job, by God.’’

The Luddites were renowned for their organisational skills, and through their transition towards collective bargaining after 1819 applied those skills to developing the British trade union movement. Many of them for the rest of their lives were involved with the social movements that followed. It was Marx and Engels who keenly identified in the passing of the 10-hour bill in 1847 that “for the first time•in broad daylight” the political economy of the working class was in the ascendency.

In 1834 the Whig Ministry, shortly after widening the vote to include the new factory owners, sanctioned the transportation of the labourers from Tolpuddle for the insolence of trade unionism, which by now was already firmly rooted elsewhere. The sour fruits of Parliamentary Reform had been anticipated by comments in the Poor Man’s Guardian by a worker from Macclesfield on 10 December 1831. He reckoned that “it mattered not to him whether he was governed by a boroughmonger, or a whoremonger, or a cheesemonger, if the system of monopoly and corruption was still to be upheld’’. What is most revealing from this period is the way British working people in the teeth of a ruthless enemy created a political force without negative and petty regional division between the North and South of our country. ■