Not content with the outcome of its 2005 Directive on recognition of professional qualifications, the European Commission is back on the warpath...

EU seeks (again) to de-skill professions

WORKERS, MAY 2012 ISSUE

The latest attempt by Brussels to tamper with national standards and qualifications is contained in a new EU Green Paper. We should know by now that anything labelled “modernising” or “simplifying” is unlikely to be good for us. The EU Green Paper entitled “Modernising Professional Qualifications” is no exception.

More than ten years ago professional bodies wishing to maintain some control over their services opted to participate in drawing up a complicated system of equivalent occupations and training frameworks. A member state would be able to regulate professions on its territory (or not) while in principle recognising qualifications obtained in another EU state.

The European Commission, Brussels: they think we’re too well qualified.

Photo: Workers

At the time the exercise was seen as providing partial protection against the destructive free movement of labour prescribed in the Treaty of Rome. In Britain some organisations worked with the British Standards Institute to ensure that national training standards were defined.

But the Commission and employers are miffed. The reason: the professions have succeeded in keeping less-qualified foreigners out, with some notable exceptions such as the case of the German agency doctor who killed his British patient (see February issue of Workers). They say that the existing directive does not offer sufficient opportunity for take-up of mobility. In its place they have launched a critique of professional qualifications, amounting to a comprehensive assault on the workers of Europe. They claim the Lisbon Treaty has given them added authority.

European employers want 16 million more skilled workers by 2020. There is a genuine need for growth, but the struggling eurozone also needs to massage unemployment figures. Construction currently accounts for 17 million jobs in the EU, education for 16 million. Then there are other industrial, trade, transport, tourism and cultural professions. All are under attack.

The Green Paper states: “Free movement of professionals can contribute to the answer to the labour shortages. It will help in satisfying the needs of customers and patients as well as providing education for the youth.” The British government agrees that the mobility of professionals is “a key part of the Single Market agenda”.

New proposals to encourage and speed up mobility by 2013 include: introducing an electronic European Professional Card; online recognition procedures; partial access to a profession; relaxing minimum training requirements; facilitating temporary mobility for “professionals accompanying consumers”; and requiring member states to justify existing regulation of professions.

The European Card and online recognition procedures are open to abuse. A professional card has been tried in Britain, but was found to be an insecure way of establishing identity and qualifications. The proposed card or certificate would not be a smart card or any sort of physical card. Application would be in the originating language via a “European professional body”, with both countries checking together via the Internal Market Information System (IMI), which was set up to implement the 2006 Services Directive.

Employers’ organisations and the British government are very keen on the card, but it shifts the balance of professional control away from the host country to the country of origin.

Some organisations are accepted in their home country as competent professional bodies when in fact their interests are entirely mercenary and their members have no qualifications whatsoever. They may authorise registration in another state based on their subjective interpretation of eligibility. In many cases mutual recognition is still open to question, particularly regarding language skill, which is checked only after recognition of primary qualification and then only if requested. It leaves the host country on the back foot, finding it hard to refuse admission in retrospect once a foreign national is on their soil.

Equally, there is uncertainty among host countries as to who should carry out the checking. Should it be a government body, the employers, or a professional standard-setting body? Should it be done on a case-by-case basis, or should blanket approval be given for a whole profession or industry? The IMI includes an alert mechanism to enable authorities to inform each other if “serious specific acts or circumstances…could cause serious damage to the health or safety of persons or to the environment”. The case of the German doctor proves this does not work.

The British government has expressed some reservations about the card scheme. It says it wants a pilot study and assurance that the cards would be tailored for specific professions. The professions themselves should just say no.

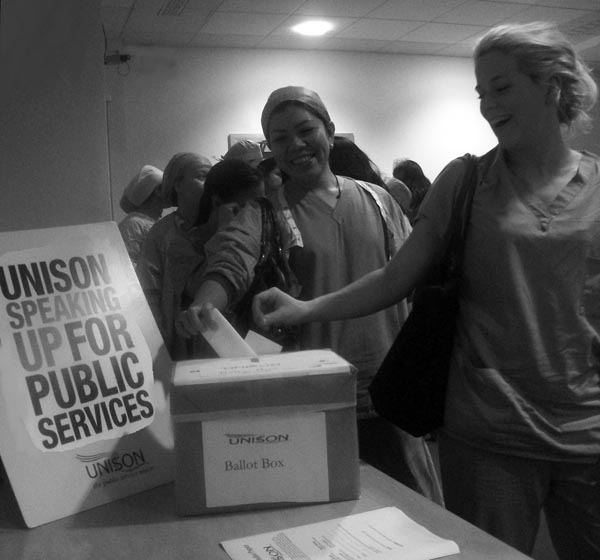

Theatre staff at St George’s Hospital, Tooting, voting in their pensions ballot last year. Health is a key battleground in the fight to ensure that services are maintained by qualified professionals.

There is widespread concern too about the principle of “partial access” to a regulated profession, which could override national standards. This was taken to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) in 2009 in the case of overlapping activities within engineering. The question was whether hydraulics specialists had the right to pass themselves off as engineers in general. It was found that the title engineer differs from country to country.

Ski instructors too questioned the right of snowboarding instructors to be included within their specialist field. The ECJ response as usual faced both ways. It concluded that these provisions “do preclude a member-state from not allowing…partial taking-up when…the differences between the fields of activity are so great that in reality a full programme of education and training is required, unless the refusal for that partial taking-up is justified by overriding reasons based on the general interest…”.

These two examples of occupations carrying high risk factors (and there are hundreds of others) show that health is by no means the only issue affecting public safety. A high profile has rightly been given to health practitioners, who have been at the forefront in highlighting the problem. But this has craftily been turned by the European Commission into a diversion away from the more general attack on all professions.

The issues with the European Card and partial access are mainly about relatively permanent settlement in another member state, where credentials must be proven. But if the recommendations of the Green Paper are implemented, professionals would no longer have to show two years of professional experience or “regulated education and training” but would simply have to send a prior declaration if requested by the host state.

Moreover, the Commission points out that if a professional wants to work abroad on a temporary or occasional basis he or she does not have to prove qualifications at all under the 2005 directive. There are no reliable statistics on which professions use this temporary mobility rule, but they are likely to be mostly unregulated and therefore particularly vulnerable to substitution by cheaper labour. It is only the organised strength of professional associations and unions insisting on their own standards that prevent this from happening.

In the case of “temporary mobility with prior check of qualifications” member states are being asked to produce a list of professions with health and safety implications. This is not because the Commission wishes to defer to the nation state in any way, but because, as it bluntly admits, that would be cheaper than doing so itself.

Less rigorous

The Commission suggests that the qualifications for some of the professions “may be disproportionate or unnecessary for the achievement of public policy objectives”. They assert that barriers are created by qualifications which they say “lack consistency with the European Qualifications Framework”. They want to reduce the number of education levels, and replace “common platforms” for existing professions with less rigorous tests.

Common platforms offered the possibility of avoiding coordination at European level of such things as aptitude tests and adaptation periods for migrant professionals provided certain criteria were met. They involved national bodies jumping through hoops measuring the length of training merely to arrive at minimum standards. They have been a waste of everyone’s time: not a single one has been completed. Now the Commission wants to abandon them altogether and instead extend automatic recognition to new professions without the need for any testing at all.

The British government “supports the move to competency-based qualifications…as this would be more in keeping with educational practices in the UK”. Will it collude with the EU by lowering British standards? It looks as though it will.

The pretext for all of this is consumer choice; or put another way, the right of the public to have their preference for high standards ignored. Quality of service, health and safety are considered only in relation to the medical and architectural professions. There is to be no universal consumer protection.

In the case of “professionals accompanying consumers”, Brussels wants to sweep away all national education and training standards. Qualifications pertaining to a specific country, region or city are treated as non-existent. There are occasions where for example a teacher, an events or sports organiser or a tour manager may accompany a group to another member state. Such a professional is said by the Commission to have been chosen by the consumer and under the new rules they would be totally exempt from all training requirements. In other words, anybody could do it. They would cease to be professionals.

Quite apart from depriving students and clients of specialist knowledge and skill, this is dangerous. Most professionals belong to an organisation providing them with public liability cover. This safety precaution could clearly be overlooked in the rush to deregulate.

The existing directive defines a regulated profession as one that requires the practitioner to have specific professional qualifications. Member states regulate access to nearly 5,000 professions based on qualification. Around 800 are regulated in Britain. With breathtaking arrogance the new EU directive requires states to better justify existing regulation within their borders, including language and other aptitude tests. The Commission will oversee this exercise, claiming further powers for itself in the process.

These demands are a prelude to sweeping away all controls and safeguards. This is an attack not only on regulated professionals, or those otherwise qualified, but on the whole working class. Those not yet qualified will find that regulated education and training courses will no longer be available. Those already seeking regulation as a trade or profession will find their path blocked.

In its response to the EU Green Paper, the British government noted the lack of a plan to reduce regulated professions. Cameron has taken the lead in calling for a reduction in their number on the grounds of cutting red tape, saying: “Outside of the health professions…the UK government would like a commitment…to remove regulations which cause unnecessary restrictions to the free movement of skilled professionals, who are often small businesses”.

That is the crux of the matter. Professionalism does not contribute to maximising business profits by lowering pay and conditions or endangering the public. Labour failed to support British workers, and signed us up to the Lisbon treaty. Now, with the approaching spring and summer conference season, our unions and organisations must confront this government with the contradictions in its relationship with the EU.

Cameron boasts of his bravery in standing up to Europe. Let him now stand up for the professionals within his own borders. ■