| The British Empire, still so often praised for its shaping of world history over the last few centuries, was at root a slave empire... |

Abolition? What abolition?

WORKERS, MAY 2007 ISSUE

The British Empire, still so often praised for its shaping of world history over the last few centuries, was at root a slave empire, held together by slave-trading between slave colonies, a world system mirroring only more grotesquely its domestic system of wage slavery. Between 1660 and 1807, British-owned ships carried 3.5 million Africans, 40,000 a year, across the Atlantic – more than any other country. British property owners were the world's chief slavers.

A part of Britain's ruling class, not the nation, owned the slave ships, the slaves and the plantations. British workers did not control their own labour power, never mind own other people. William Cobbett noted that in 1832, "white men are sold, by the week and the month all over England. Do you call such men free, on account of the colour of their skin?" Black chattel slavery and white wage slavery were parts of the same system.

Wage slaves at home

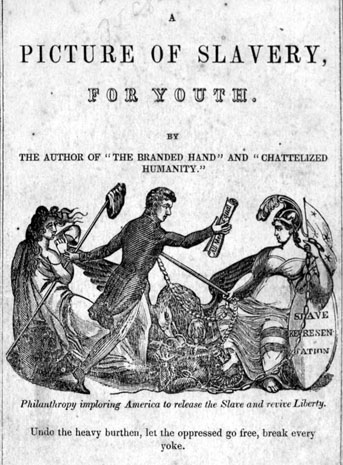

By the 19th century the more powerful part of Britain's ruling class were those who exploited wage slaves at home. They led the abolitionist movement, ignoring the eighteen-hour days worked by children in Bradford's mills. They backed the laws that attacked trade unions and suspended Habeas Corpus. They funded their foreign philanthropy by increasing the exploitation of their white slaves at home. The trade unionist Oates said, "The great emancipators of negro slaves were the great drivers of white slaves. The reason was obvious. The labour of the black slaves was the property of others. The labour of the white slaves they considered their own." As the Derbyshire Courier noted, "We make laws to provide protection to the Negro: let us not be less just to the children of England."

Bronterre O'Brien wrote, "What are called the working classes are the slave populations of the civilized countries." From birth, workers were mortgaged to the owners of capital and land, forced into wage slavery. Britain's property owners gained far more profit from their 16 million wage slaves than from their million chattel slaves. O'Brien again, "We pronounce there to be more slavery in England than in the West Indies ... because there is more unrequited labour in England."

The empire was based on exploiting wage slaves and used the free movement of goods, capital and labour to extend its exploitation. The wars of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries were fought to keep, or add to, Britain's imperial and slave-trading conquests. For example, in the 1790s, British slave owners united with French slave owners to try to defeat Haiti's revolution. The government sent more soldiers to the West Indies, and lost more, than it had when trying to crush America's independence. Of the 89,000 sent, 45,000 died, as did 19,000 sailors. France lost 50,000 dead. Haiti's freed slaves defeated the armies of the two greatest slaver powers, but the British forces laid waste to the island, destroying almost all its sugar plantations.

Fine words, but the truth is that abolition began to serve the employers better than slavery.

By 1807 the slave trade was becoming less profitable: it employed only one in 24 of Liverpool's trading ships and the West Indies sugar industry was dying. All the plantations were running at a loss; many had been abandoned. Two-thirds of the slaves carried in British ships were bought by Britain's imperial rivals France and Spain, to grow sugar which undercut West Indies-grown sugar on the vital Continental market. All these factors opened the way to the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act; from 1 May 1807, no more slave ships sailed from Britain.

But the government let the British Army and the Royal Navy force slaves into unpaid military service and buy and sell slaves until 1812, breaking its own law. The office of Jamaica's Governor General wrote in August 1811, "I am commanded by the Commander of the Forces to direct that you will go on purchasing Negroes for the Kings Service after you have completed your own regiment. The men so purchased are only to receive rations and slop clothing, no pay is to be issued to them until they are further disposed of."

Further, in 1814, Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh agreed that Bourbon France could resume slave trading to restock her colonies and to resupply Britain's West Indies plantations. As Lord Grenville said, "We receive a partial contract at the Congress of Vienna by which the British Crown has sanctioned and guaranteed the slave trade."

Slavery lost its former importance to the metropolitan economy. The slave colonies took an ever-smaller share of Britain's exports. From 1820 the slump in the West Indies grew worse and worse. In 1832, an official wrote that the West Indies system "is becoming so unprofitable when compared with the expense that for this reason only it must at no distant time be nearly abandoned."

Revolts at home

The years 1830-32 also saw the Swing Rising in Britain, revolution in France, a major slave revolt in Jamaica and the parliamentary Reform Act. All led to the 1833 Slave Emancipation Act, which freed the 540,000 slaves in the British West Indies. Parliament gave the planters £20 million (£1 billion in today's money) as compensation for the loss of their slaves. The working class paid the money in tax, though they pointed out that the Church should have paid, as it owned so many slaves itself and as its priests justified the slavery of both black and white, at home and abroad. The Empire then imposed another form of servitude on the "freed" slaves of the West Indies – compulsory six-year "apprenticeships". Later in the century, it used indentured labour, with workers forcibly imported from India.

Slavery had been profitable in the 18th century; abolition was even more profitable in the 19th. The effort to "stop the foreign slave trade" was designed to damage rival empires and to protect the West Indies planters, now denied annual slave imports, from competition by sugar producers Cuba and Brazil, still reliant on buying slaves. The suppression of the slave trade on Africa's West and East coasts brought ever-closer control of West and East Africa, at first by private com-panies like the British East Africa Company, later by the Empire itself. Abolition was a weapon to expand the empire.

Throughout the century, the Empire continued to steal people, land and resources from Africa, reinforcing slavery there and killing millions of African people. The Empire continued to contribute to and profit from the slave trade well into the twentieth century. As Marx wrote, slavery is "what the bourgeoisie makes of itself and of the labourer, wherever it can without restraint model the world after its own image."

Abolitionism was an early form of the fake internationalism we see today – LiveAid, Live Earth, Blairite calls to intervene everywhere, Oxfam's delusions about Britain being "a force for good on the world stage". We would be satisfied if Britain was a force for good in Britain, and the world better served.