It began with the reasonable demand for a 40-hour week, led to a demonstration by 35,000 workers at Glasgow’s City Chambers – and howitzers around the city centre…

The day the Army was sent to the streets of Glasgow

WORKERS, MARCH 2010 ISSUE

NINETY YEARS ago in the aftermath of years of capitalist crisis and the “War to end all Wars”, the British government had the military on alert to deal with a working class response it feared. Organised workers had forged strong links between centres of heavy industry, particularly in Sheffield, Newcastle and Glasgow.

The ties were strongest among those working in engineering and shipbuilding. Even in the midst of the First World War, those workers had resisted the imposition of the Munitions Act, the Dilution of Labour Act and Defence of the Realm Act, all giving government draconian powers to negate long-fought-for pay rates and conditions for skilled work, and to crack down on opposition.

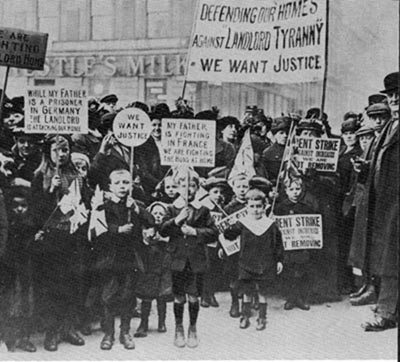

Social unrest grew too, with well organised campaigns such as the Glasgow Rent Strike of 1916. One of the leaders was suffragette and communist Helen Crawfurd, who helped forge close links between the Clyde Workers Committee (CWC) and the Glasgow Women’s Housing Association.

Organisation

Organisation was key, too, in the growth of the CWC itself, bringing together shop stewards, delegates and the Trades Union Councils. Its strength was demonstrated by the chasing off stage of the Prime Minister of the day, Lloyd George, at a showcase rally at Christmas, 1915, intended to promote the need for his various draconian Acts. The 3000 shop stewards and union delegates then took over the meeting.

The only newspaper to report this, FORWARD (with a circulation of over 30,000), was suppressed by the military. The smaller VANGUARD , inspired by Bolshevism, was also closed. Copies of FORWARD were even confiscated from newsagents and regular readers’ homes. However, only a week later, the CWC launched its own journal THE WORKER – ORGAN OF WORKERS’ COMMITTEES OF SCOTLAND. It ran to five issues before the editorial team and printer were arrested and most jailed for a year. It had featured the defiant statement:

“The British authorities having adopted the methods of Russian despotism, British workers may have to understudy Russian revolutionary methods of evasion… but here is THE WORKER once again, symbolical of the fact that the cause of Labour can never be suppressed. It may be and has been bamboozled, hoodwinked, side-tracked and misled; it may be browbeaten, persecuted and driven underground, but it cannot be killed; and just when its enemies think they have finally subdued and made an end of it, it emerges more virile and vigorous than ever.”

Workers organising was nothing new — the weavers of Glasgow’s Calton district were strong enough to engage in a long and bitter dispute over wages and basic justice in 1787, only ending when several were killed by government forces. An insurrection in 1820 had ended in death and deportation, and Glasgow Trades Union Council was one of the earliest in Britain over 150 years ago.

By 1918, the combination of people’s high expectations of peacetime and demands of the returning troops and sailors gave the government a dread of the influence of the world-changing actions carried out by workers in other lands.

Particularly on their minds were the 1916 uprising in Ireland, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 in Russia and the build up to what was an almost successful revolution in Germany in 1919.

|

|

| Left: Glasgow rent strike, 1916. Right: three years on, and tanks are stationed in Glasgow on Churchill’s orders as mass action grew. | |

Hence the reasonable demand for a 40-hour working week led to what became known as Black Friday, 5 February 1919. That day months of CWC agitation culminated in a mass demonstration of over 35,000 workers at the City Chambers in George Square in Glasgow city centre. It was attacked viciously by police and serious rioting ensued.

Tanks and troops

Its Britain-wide implications were made clear by the actions of Churchill and his Cabinet in ordering tanks and troops into the city. Local soldiers were confined to barracks, while the troops brought in were from well outwith the area. Machinegun nests on rooftops and even howitzers were positioned around the city centre.

However, although well organised and with a popular following, the workers committees were from a defensive tradition, of a trade union nature. They were coping with appalling conditions and the fear of looming mass unemployment. And there was nothing in the form of a Bolshevik or communist party in Britain at that time to inspire the struggle to go to a more ambitious stage.

It was perhaps no accident that diversions into nationalism and separatism – aimed at smashing the necessary British class unity – were concocted at this time. 1920 saw the formation of the Scots National League, John MacLean entering the cul-de-sac of Scottish republicanism and poet Hugh MacDiarmid writing his PLEA FOR A SCOTTISH FASCISM calling for socialism to develop “a fascist rather than a Bolshevik spirit”.

Others, including speakers at the 1915 and 1919 rallies, walked off into benign parliamentary social democracy. Kirkwood became Baron Bearsden; Mitchell hardly spoke in parliament; Maxton faded with the Independent Labour Party and Gallagher was an isolated communist voice at Westminster.

Helen Crawfurd went on to play a leading role in the Workers International Relief Organisation, set up to defend the Russian Revolution, having met Lenin in 1920. She was politically active until her death in 1954, being elected as a communist to the town council in Dunoon, Argyllshire, in 1946.